Science

CU Boulder Team Uncovers Rapid Retreat of Antarctica’s Hektoria Glacier

A research team from the University of Colorado Boulder has revealed the alarming speed at which the Hektoria Glacier in Antarctica retreated, losing approximately half of its mass within just two months. This unprecedented phenomenon marks the fastest recorded retreat of a grounded glacier, as the team documented a retreat of about 15.5 miles between January 2022 and March 2023.

The investigation began when Naomi Ochwat, a research affiliate at CU Boulder, observed the Hektoria Glacier’s rapid decline, a retreat unlike any previously recorded. Intrigued, Ochwat and her colleagues set out to understand the mechanisms behind this extraordinary loss of ice. Their findings suggest that if similar processes occur on larger glaciers, the implications could be significant for global sea levels.

Understanding Glacier Dynamics

The Hektoria Glacier, measuring about 8 miles across and 20 miles long, is relatively small by Antarctic standards. According to Ted Scambos, a senior research scientist at CU Boulder, while the glacier’s impact on sea level rise is currently minimal—amounting to fractions of a millimeter—its rapid retreat reveals crucial insights about glacial dynamics.

“This process highlights what can happen during glacial retreat,” Scambos noted. “We need to investigate other areas of Antarctica that might exhibit similar geometries and retreat behaviors.”

A key factor in the glacier’s retreat was the destabilization of fast ice, which previously provided essential support to the glacier’s ice tongue. Warmer conditions led to the breaking away of this fast ice, causing the glacier’s floating ice tongue to begin crumbling into the ocean. Scambos explained that this destabilization process is not unusual, but the speed and scale observed in Hektoria Glacier are unprecedented.

The Mechanism Behind the Retreat

The research team discovered that the rapid retreat was primarily driven by a calving process associated with the glacier’s ice plain, a flat area of bedrock beneath the glacier. As warmer waters thinned the glacier, ice resting on the bedrock began to rise, allowing water to flow underneath and increase pressure, leading to large slabs of ice breaking off in a cascading manner.

“This mechanism, where the ice plain thins and starts to float, has not been documented before,” Ochwat stated. The study utilized satellite-derived data, including images and elevation profiles, to monitor the glacier’s changes over time.

The implications of this research extend beyond the immediate area. Ice sheets hold vast quantities of water, and their melting could lead to significant increases in sea level. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, nearly 30% of the U.S. population resides in coastal regions where rising sea levels contribute to flooding and erosion. Furthermore, the United Nations highlights that eight of the world’s ten largest cities are situated near coastlines, underscoring the global significance of these findings.

“The dynamics of Antarctica are interconnected with the rest of the world,” Ochwat concluded. “Research in this area is essential as we strive to understand the broader impacts of glacial retreat and climate change.”

As scientists continue to investigate the Hektoria Glacier and similar regions, the findings could offer critical insights into the future of Antarctica’s ice sheets and their potential effects on global sea levels.

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoNew ‘Star Trek: Voyager’ Game Demo Released, Players Test Limits

-

World2 months ago

World2 months agoGlobal Air Forces Ranked by Annual Defense Budgets in 2025

-

World2 months ago

World2 months agoMass Production of F-35 Fighter Jet Drives Down Costs

-

Science2 weeks ago

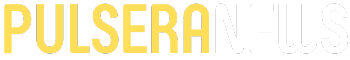

Science2 weeks agoALMA Discovers Companion Orbiting Giant Red Star π 1 Gruis

-

World2 months ago

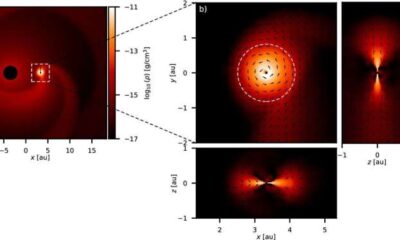

World2 months agoElectrification Challenges Demand Advanced Multiphysics Modeling

-

Business2 months ago

Business2 months agoGold Investment Surge: Top Mutual Funds and ETF Alternatives

-

Science2 months ago

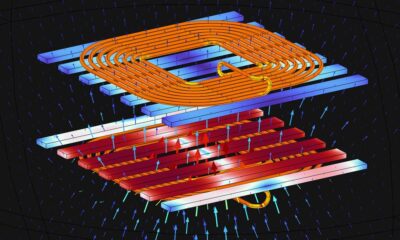

Science2 months agoTime Crystals Revolutionize Quantum Computing Potential

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoDirecTV to Launch AI-Driven Ads with User Likenesses in 2026

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoFreeport Art Gallery Transforms Waste into Creative Masterpieces

-

Business2 months ago

Business2 months agoUS Government Denies Coal Lease Bid, Impacting Industry Revival Efforts

-

Health1 month ago

Health1 month agoGavin Newsom Critiques Trump’s Health and National Guard Plans

-

Lifestyle1 month ago

Lifestyle1 month agoDiscover Reese Witherspoon’s Chic Dining Room Style for Under $25