Science

ESA Plans Mission to Catch Unseen Comet in Solar System

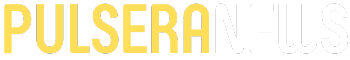

The European Space Agency (ESA) is gearing up for an ambitious mission aimed at exploring a comet that has not yet been discovered. Known as the Comet Interceptor (CI), this innovative mission intends to investigate a dynamically new comet (DNC) entering the inner solar system for the first time. As outlined in a recent paper by lead author Professor Colin Snodgrass from the University of Edinburgh, the success of this mission hinges on meeting a complex set of conditions.

CI represents an ESA F-Class mission, designed for rapid development and launch. It will position itself at the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point, waiting for a suitable target comet. The mission could also potentially observe an interstellar object, such as 3I/ATLAS, as it passes through the solar system. However, the chances of encountering an interstellar object during CI’s operational window are exceptionally low. In contrast, DNCs are more frequently observed; from 1898 to 2023, 132 DNCs have been recorded.

The viability of CI’s mission depends on a range of factors. The authors of the paper note that many comets are extremely faint and are often only discovered shortly before they approach the inner solar system. To enhance the likelihood of finding a suitable target, the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) at the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is expected to identify more DNCs. This could provide the CI mission team with the necessary advance notice to assess potential candidates thoroughly.

Nonetheless, the discovery of a comet by LSST does not guarantee it will be bright enough for scientific study as it nears the Sun. Additionally, there is the risk that a comet could disintegrate before CI gets close enough for observation. With the mission limited to a single target, the unpredictability involved adds considerable complexity to the selection process.

To navigate these uncertainties, Snodgrass and colleagues employed game theory to analyze potential scenarios. They established basic constraints for the mission, including a limited “delta-v,” or the energy necessary to reach the comet. This delta-v is calculated at 1.5 km/s, which is relatively modest by interplanetary mission standards. The CI mission must intercept a comet between 0.9 and 1.2 astronomical units (au) from the Sun, coinciding with Earth’s orbital path. The spacecraft must also maintain a Sun angle of between 45° and 135° for optimal solar panel efficiency.

Another critical factor is the comet’s speed during the fly-by, which cannot exceed 70 km/s. If the comet travels faster, the resulting dust could damage the smaller probes released to analyze the comet’s coma. Furthermore, the comet must produce an adequate amount of gas for study, without overwhelming the probes. The authors suggest that Halley’s Comet serves as a reasonable benchmark for the required outgassing levels.

The analysis of historical comets revealed valuable insights for the selection process. The researchers initially focused on scientifically significant comets, filtering for those actively approaching the solar system with a brightness of magnitude 10. This yielded nine potential candidates, but further investigation demonstrated that none were reachable under the mission’s engineering constraints.

Consequently, the team shifted their approach to prioritize feasibility. By focusing on candidates that could be reached within the 1.5 km/s delta-v budget while still meeting activity requirements, they narrowed the list down to three comets. Among them, C/2001 Q4 (NEAT), discovered in 2001, showed promise. This comet exhibited good activity levels and fell within the delta-v constraints. However, it posed a challenge due to its relatively high fly-by speed of 57 km/s, which could jeopardize the probes’ integrity and limit data collection time.

Looking ahead, the likelihood of finding an ideal candidate within the 2-3 year window of CI’s mission appears slim. The mission operators may ultimately have to settle for a “good enough” target and gather whatever data is possible. This situation reflects the inherent limitations of missions where the final target remains unknown at the design and launch stages.

With the LSST expected to launch in 2029, there is hope that it will aid in identifying suitable targets for CI. If fortune favors the endeavor, the mission may even encounter an interstellar visitor worthy of study. In such a scenario, an intriguing name for the object might be “Rama.”

-

Science3 weeks ago

Science3 weeks agoALMA Discovers Companion Orbiting Giant Red Star π 1 Gruis

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoNew ‘Star Trek: Voyager’ Game Demo Released, Players Test Limits

-

World2 months ago

World2 months agoGlobal Air Forces Ranked by Annual Defense Budgets in 2025

-

World2 months ago

World2 months agoMass Production of F-35 Fighter Jet Drives Down Costs

-

World2 months ago

World2 months agoElectrification Challenges Demand Advanced Multiphysics Modeling

-

Business2 months ago

Business2 months agoGold Investment Surge: Top Mutual Funds and ETF Alternatives

-

Science2 months ago

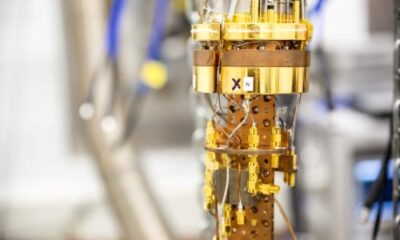

Science2 months agoTime Crystals Revolutionize Quantum Computing Potential

-

Politics1 month ago

Politics1 month agoSEVENTEEN’s Mingyu Faces Backlash Over Alcohol Incident at Concert

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoDirecTV to Launch AI-Driven Ads with User Likenesses in 2026

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoFreeport Art Gallery Transforms Waste into Creative Masterpieces

-

Business2 months ago

Business2 months agoUS Government Denies Coal Lease Bid, Impacting Industry Revival Efforts

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoGavin Newsom Critiques Trump’s Health and National Guard Plans