Politics

East Germany’s Legacy: Socialism’s Need for Genuine Democracy

The legacy of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), which was absorbed by West Germany 35 years ago, continues to provoke discussion about the relationship between socialism and democracy. This examination reveals a complex history marked by economic achievements and political limitations.

The GDR was notable for its innovative approaches, including the production of exceptionally durable beer glasses by Superfest Glas and efficient housing developments in Marzahn, a district built in just a decade to accommodate 160,000 residents. The state also provided substantial support for international causes, such as solidarity with Palestine and assistance to anti-colonial movements in Africa. These accomplishments were rooted in a planned economy that prioritized societal needs over profit maximization.

While some socialists defend the GDR as a valid example of a workers’ state, it is essential to recognize that a planned economy alone does not equate to true socialism. As noted in discussions regarding the definition of socialism, it represents a transitional phase between capitalism and communism, characterized by the working class exerting control over societal management.

The Internationale Forschungsstelle DDR (IFDDR) argues that the GDR was indeed socialist and emphasizes the presence of democratic elements, suggesting that the “D” in GDR reflects genuine democratic practices. They highlight mechanisms such as workers’ rights to participate in factory management and a system that allowed citizens to communicate with their representatives. However, the GDR’s electoral framework presented significant limitations, as citizens could only vote for a single list presented by the ruling party, resulting in overwhelming majorities that masked the lack of true democratic choice.

Elections in the GDR, held every four to five years, demonstrated a façade of democracy. While the ruling party, the National Front, reported victories with percentages ranging from 99.95 to 99.46, these figures were often accompanied by allegations of electoral fraud. This raises important questions about the authenticity of democratic processes under such conditions.

The criticisms of parliamentary democracy, particularly within a capitalist context, focus on its often superficial nature. A Marxist perspective calls for more robust forms of governance, such as workers’ councils or soviets, which empower workers to elect representatives who hold both legislative and executive powers. In contrast, the GDR’s version of democracy fell short, resembling a poorly constructed imitation of bourgeois democratic systems.

The IFDDR claims that economic authority was devolved to the working masses, yet lacks concrete examples of how economic decision-making occurred. A notable policy change in 1971 under Erich Honecker emphasized consumer goods and housing over heavy industry, but the extent of workers’ involvement in such decisions remains unclear. The assertion of overwhelming support for this policy shift contradicts the principles of genuine democratic engagement.

Moreover, the GDR maintained a significant state security apparatus, known as the Stasi, which employed over 91,000 full-time staff and utilized countless informants to surveil and control the population. Resources were disproportionately allocated to suppress dissent rather than fostering cultural development or addressing social needs, revealing a critical flaw in the system’s priorities.

In reflecting on the GDR’s societal structure, journalist John Peet, who spent 35 years in East Germany, remarked that while the state provided essential services like housing and education, it operated under a model of “benevolent paternalism.” He criticized the lack of public discourse in decision-making, suggesting that important choices were made without sufficient input from the population. Peet’s experiences highlight the disconnect between the government and the people, ultimately contributing to a culture of conformity and disengagement.

The lessons drawn from the GDR’s experience emphasize that while a planned economy has the potential to greatly enhance the quality of life, the absence of authentic democratic practices can lead to the stagnation of socialist ideals. Understanding this interplay between economic planning and democracy is crucial for contemporary discussions on socialism, as it underscores the need for genuine worker participation and accountability in governance.

As the world continues to grapple with the legacies of past political systems, the GDR serves as a reminder of the importance of integrating democratic principles within socialist frameworks. Achieving a balance between economic planning and democratic engagement remains a vital pursuit for those advocating for a more equitable society.

-

Science1 month ago

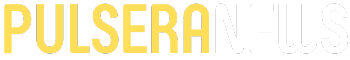

Science1 month agoALMA Discovers Companion Orbiting Giant Red Star π 1 Gruis

-

Politics2 months ago

Politics2 months agoSEVENTEEN’s Mingyu Faces Backlash Over Alcohol Incident at Concert

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoNew ‘Star Trek: Voyager’ Game Demo Released, Players Test Limits

-

World2 months ago

World2 months agoGlobal Air Forces Ranked by Annual Defense Budgets in 2025

-

World2 months ago

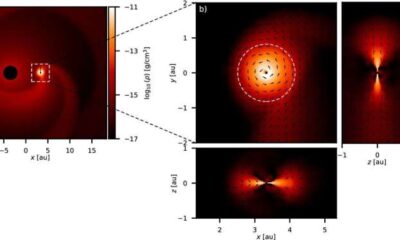

World2 months agoElectrification Challenges Demand Advanced Multiphysics Modeling

-

World2 months ago

World2 months agoMass Production of F-35 Fighter Jet Drives Down Costs

-

Business2 months ago

Business2 months agoGold Investment Surge: Top Mutual Funds and ETF Alternatives

-

Science2 months ago

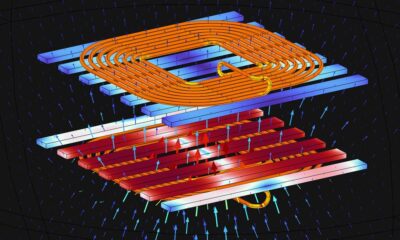

Science2 months agoTime Crystals Revolutionize Quantum Computing Potential

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoDirecTV to Launch AI-Driven Ads with User Likenesses in 2026

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoFreeport Art Gallery Transforms Waste into Creative Masterpieces

-

Business2 months ago

Business2 months agoUS Government Denies Coal Lease Bid, Impacting Industry Revival Efforts

-

Health2 months ago

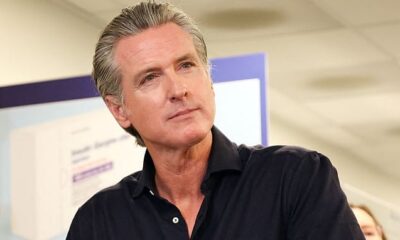

Health2 months agoGavin Newsom Critiques Trump’s Health and National Guard Plans