Science

Animal Families Defy Norms Found in Children’s Literature

Children’s literature often portrays animals as part of neat nuclear families, featuring a mother, father, and their young. Classic examples include Fantastic Mr. Fox, 101 Dalmatians, and popular modern titles like Peppa Pig and Bluey. This representation may alienate children from non-traditional family backgrounds. In contrast, the animal kingdom showcases a wide variety of family structures, emphasizing that parenting is far more complex than the typical family unit depicted in these stories.

Parental Roles in the Animal Kingdom

In the realm of animal behavior, biparental care—where both a male and female raise their offspring together—is predominantly observed in birds and is rare among fish, invertebrates, and mammals. A notable example is the mute swan, where both parents share tasks such as incubating eggs, feeding cygnets, and teaching them independence.

However, single-parenting is the most prevalent family structure within the animal kingdom. Typically, males compete for access to females since females invest more in reproduction. For instance, in many mammal species, females are responsible for gestation and nurturing. In species like leopards, females often raise their young alone. Research indicates that approximately 90% of mammals exhibit single-parenting behaviors. While children’s literature occasionally reflects this, such as in The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter, stories focusing on single mothers are less common than found in nature, where females often benefit from raising offspring independently.

In some instances, males take on parenting roles, particularly in fish and amphibians. The midwife toad is one example where the male carries fertilized eggs on his back until they are ready to hatch. Another fascinating example is the Darwin’s frog, where the male nurtures tadpoles in his vocal sac for several weeks until they can survive independently. This allows females to concentrate on feeding, increasing their capacity for producing more eggs.

Same-Sex Relationships and Cooperative Parenting

Same-sex couplings have been documented in over 500 species, including dolphins, giraffes, and bonobos. While lifelong homosexuality is rare in the wild, permanent male-male pairings have been observed in sheep. Female albatrosses sometimes reject males after fertilization, opting to engage in female-female relationships when raising their young.

One notable example of same-sex parenting occurred with Roy and Silo, a pair of chinstrap penguins at the Central Park Zoo. Their bond was so strong that their keeper provided them with an egg to raise together, which later inspired the children’s book And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson. Though their relationship ultimately ended when Silo was attracted to a female penguin named Scrappy, their story remains a poignant reflection of love and family dynamics beyond traditional norms.

Communal parenting also occurs in species such as elephants, where family units comprise related females and their calves. Led by a matriarch, these groups engage in allomothering, a practice where sisters and grandmothers assist in caring for the young. This cooperative breeding approach is not limited to one sex. For instance, meerkats often work together to raise their siblings, with some individuals choosing to remain with their parents instead of breeding independently.

The animal kingdom also features instances of fostering and adoption. The common cuckoo is famous for laying its eggs in the nests of other species, forcing the unsuspecting foster parents to raise the cuckoo chick. Deliberate adoption can even occur between different species; in 2004, a wild capuchin monkey was observed caring for a common marmoset.

Children’s literature reflects this diversity in relationships, as seen in The Odd Egg by Emily Gravett, where a mallard adopts an egg that eventually hatches into an alligator.

Animals also form strong friendships, particularly among social species. For example, bachelor herds of red deer often remain together until reaching sexual maturity, supporting each other as they grow. Young swifts engage in “screaming parties,” forming protective groups while preparing to breed in the future.

Finally, there are species that exhibit little to no parental care. In these cases, numerous offspring are born to ensure that at least some survive independently. Fish, reptiles, and certain invertebrates like butterflies and spiders exemplify this strategy. Certain solitary wasps, for instance, trap paralyzed grasshoppers in their nests and abandon them, ensuring a food supply for their larvae upon hatching. In these nests, up to 75% of wasp larvae may end up as food for their siblings.

Overall, the array of parenting styles in the animal kingdom starkly contrasts the tidy family units typically portrayed in children’s literature. By understanding these diverse family dynamics, readers can appreciate the complexity of relationships in nature, which often defy conventional norms.

-

World3 weeks ago

World3 weeks agoGlobal Air Forces Ranked by Annual Defense Budgets in 2025

-

World3 weeks ago

World3 weeks agoMass Production of F-35 Fighter Jet Drives Down Costs

-

Science3 weeks ago

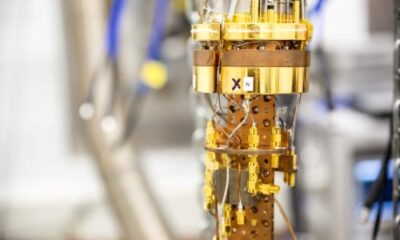

Science3 weeks agoTime Crystals Revolutionize Quantum Computing Potential

-

World3 weeks ago

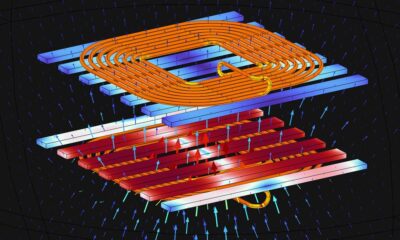

World3 weeks agoElectrification Challenges Demand Advanced Multiphysics Modeling

-

Top Stories3 weeks ago

Top Stories3 weeks agoDirecTV to Launch AI-Driven Ads with User Likenesses in 2026

-

Lifestyle3 weeks ago

Lifestyle3 weeks agoDiscover Reese Witherspoon’s Chic Dining Room Style for Under $25

-

Top Stories3 weeks ago

Top Stories3 weeks agoNew ‘Star Trek: Voyager’ Game Demo Released, Players Test Limits

-

Entertainment3 weeks ago

Entertainment3 weeks agoFreeport Art Gallery Transforms Waste into Creative Masterpieces

-

Health3 weeks ago

Health3 weeks agoGavin Newsom Critiques Trump’s Health and National Guard Plans

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoLanguage Evolution: New Words Spark Confusion in Communication

-

Lifestyle3 weeks ago

Lifestyle3 weeks agoLia Thomas Honored with ‘Voice of Inspiration’ Award at Dodgers Event

-

Business3 weeks ago

Business3 weeks agoGold Investment Surge: Top Mutual Funds and ETF Alternatives